What if I Notice Blood in my Stool?

What if I notice blood in my stool? Lower gastrointestinal bleeding, commonly abbreviated LGIB, refers to any form of bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract. LGIB is a common ailment seen at emergency departments.[1] It presents less commonly than upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). It is estimated that UGIB accounts for 100–200 per 100,000 cases versus 20–27 per 100,000 cases for LGIB.Approximately 85% of lower gastrointestinal bleeding involves the colon, 10% are from bleeds that are actually upper gastrointestinal bleeds, and 3–5% involve the small intestines. The mortality rate for LGIB is between 2–4%.

I See Blood in my Stool

A lower Gastrointestinal Bleed is referred as any bleed that occurs distal to the ligament of Treitz and superior to the anus. This includes the last 1/4 of the duodenum and the entire area of the jejunum, ileum, colon, rectum, and anus.

The stool of a person with a lower gastrointestinal bleed is a good (but not infallible) indication of where the bleeding is occurring. Black tarry appearing stools medically referred to as melena usually indicates blood that has been in the GI tract for at least 8 hours. Melena is four-times more likely to come from an upper gastrointestinal bleed than from the lower GI tract; however, it can also occur in either the duodenum and jejunum, and occasionally the portions of the small intestine and proximal colon. Bright red stool, called hematochezia, is the sign of a fast moving active GI bleed.[1] The bright red or Maroon color is due to the short time taken from the site of the bleed and the exiting at the anus. The presence of hematochezia is six-times greater in a LGIB than with a UGIB.

Occasionally, a person with a LGIB will not present with any signs of internal bleeding, especially if there is a chronic bleed with ongoing low levels of blood loss. In these cases, a diagnostic assessment or pre-assessment should watch for other signs and symptoms that the patient may present with. These include, but are not limited to, hypotension, tachycardia, angina, syncope, weakness, confusion, stroke, myocardial infarction/heart attack, and shock.

Causes

- Coagulopathy — specifically a bleeding diathesis

- Colitis

- Hemorrhoids

- Angiodysplasia

- Neoplasm — cancer

- Diverticular disease — diverticulosis, diverticulitis

The following are possible diagnosis of a LGIB:

- Hemorrhoids are a common occurrence; however, rarely they have been known to rupture and result in a massive hemorrhage. Causes for this include frequent or chronic constipation, straining to have a bowel movement, diets low in fiber, and pregnancy. It may present with small amounts of bright red bleeding.

- Anal fissures

- Rectal foreign bodies

- Ulcerative colitis

- Crohn’s disease

- Pseudomembranous colitis

- Infectious diarrhea

- Radiation colitis

- Diverticulosis

- Mesenteric ischemia

- colonic polyps

- colon cancer

Diagnosis

Evaluations will most often be conducted by either a clinic triage nurse, emergency department nurse, and/or a physician or other clinican. The initial assessment will include the appearance of the individual, their vital signs, and mental status. A patient history will help reveal a disposition or history of LGIBs or potential differential diagnosis.

Orthostatic vital signs are often used as an indicator of hypovolemia.

Laboratory test will also help give indications of a LGIB. Hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelets are very good physical signs of hypovolemia or blood loss anemia. Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and INR will also help determine the body’s current ability to clot.

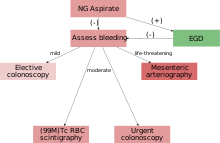

Aspiration of the stomach contents by way of a nasogastric tube (NG tube) will help differentiate between either a UGIB and a LGIB. A negative presence of blood will help to rule out an UGIB.

Differential diagnosis

A differential diagnosis is a systematic method used to identify unknowns. With the use of a differential diagnosis, physicians or other clinicians begin to rule out what the illness is not to narrow the diagnosis of the specific disease process, as with a lower gastrointestinal bleed.

Diverticulosis, Angiodysplasia, Infectious Colitis, Ischemic Colitis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Neoplasms, Radiation Telangiectasia and Proctitis, and NSAID Enteropathy and Colopathy are the causes of LGIB in adults.

The most common cause of massive bleeding in pediatric patients is Meckels Diverticulum. Anorectral disease (hemorrhoids and fissures) causes less severe bleeding in pediatric patients.

Management

In most cases requiring emergency hospital admission, the bleeding will resolve spontaneously. If a patient is suspected of having severe blood loss they will most likely be placed on a vital sign monitor and administered oxygen either by nasal cannula or simple face mask. An intravenous catheter will be placed into an easily accessible area and IV fluids will be administered to replace lost volume. Predicting which patients will suffer adverse outcomes, complications or severe bleeding can be difficult. One recent study identified poor renal function (creatinine > 150 μm), age over 60 years, abnormal haemodynamic parameters on presentation (low blood pressure) and persistent bleeding within the first 24 hours as risk factors for worse outcome.

Surgical intervention is warranted in some cases. It is most likely that a surgical consult will be ordered if the patient is unable to be stabilized by non-invasive techniques, or a perforation is found that requires surgery.

The best course of action is to call us immediately so we can set up an examination for your health and safety. Call 210-268-0124 or visit www.stoneoakgi.com

>

>